The architects and developers behind some of Canada’s new Indigenous-focused projects are designing spaces that harmonize with their natural landscapes, setting a higher standard for how urban buildings impact the environment and their surrounding communities.

There are vast opportunities for non-Indigenous business leaders to partner with Indigenous-owned businesses to create spaces that articulate Indigenous values into the planning and design phases, as an Urban Land Institute event in February showcased.

Yet there remains a resistance to partner, despite Indigenous and non-Indigenous people building the country together, said moderator Tim Coldwell, president of Chandos Construction.

Two Row Architect Founder Brian Porter relates this to factors such as Canada’s preference for a resource-based economy through the export of natural materials.

“They are bought back and value-added products from our international trade partners,” he said. “This is counter-intuitive to Indigenous values. We need to become a nation that adds value to the resources we extract and reaps the benefits of the jobs that come along with it.”

Legal challenges also impact business deals, along with Canada’s reluctance to honour signed treaties.”I don’t think these hurdles will be resolved in my lifetime, but one way forward may be to have less formal consultations between opposing sides,” suggested Porter. “Instead, let’s have more business conversations around the table.”

Here are five significant development partnerships with Indigenous stakeholders that are creating turning points in Canadian cities.

Toronto Public Library, Dawes Road Branch, Toronto

The south east corner of the Toronto Public Library’s Dawes Road branch. Rendering by Smoke Architecture and Perkins&Will.

The Toronto Public Library Dawes Road Branch is a vision from Smoke Architecture and Perkins&Will. Built in 1976, it will be redeveloped into a city-operated community hub on the corner of Chapman Avenue and Dawes Road, and rooted in Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Huron-Wendat culture.

Integrated public spaces are inspired by the movement of water. The roof garden makes space for a sacred fire. Interiors gesture to the Haudenosaunee longhouse. On the third level, a roundhouse—based on an Anishinaabe architectural typology and traditionally a place to gather and share knowledge for the community—is a circular space in the heart of the building that is rooted to the earth, defining the central bay of the longhouse, the place of the clan mother.

The exterior is wrapped with a star blanket, symbolizing the unity between the Social Development Finance & Administration coming together with the community hub it will operate in the Toronto Public Library. “That star symbolizes the presence and attention and support of the community, which comes together as a patchwork of multiple, unique individuals, but also represents their ancestors which are recorded in the stars,” said Eladia Smoke, principal architect and owner of Smoke Architecture.

A view from the east opens the blanket to the community, displaying the roundhouse prominently, she said. “We heard from our participants that it was critical to have a safe place of Indigenous knowledge sharing in a urban location.”

Jericho Lands, Vancouver

Rendering by MST Development Corporation.

Vancouver’s three nations—Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh—have regained ownership of traditional territory for future generations through the formation of MST Development Corporation. They bought the 92-acre Jericho Lands—partially co-owned with the Canada Lands Company—located in Vancouver’s West Point Grey neighbourhood.

Dennis Thomas, senior business development manager for the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, said they are collaborating with Vancouver, in turn, helping to build their Indigenous economy and ecosystems while easing the city’s affordable housing crisis.

Design concepts, released last fall, propose 10 million square feet of new development, 20 acres of new park land and enough housing for 15,000 to 18,000 people—20 per cent social housing and 10 per cent market rental, with a proportion of below market rental.

As cultural liaisons, the nations brought artistic graphic illustrators into their communities to conceptualize the needs and visions of elders and knowledge-holders. They identified core themes: wind, water, fire, the transfer of knowledge. “Putting an elder centre next to the daycare, so the elders can get energy from the kids; that was so important to our people growing up,” said Thomas.

In the rendering, three prominent “sentinel” buildings represent each First Nation, viewable from all directions. Lines in the topography of the “weave” proposal symbolize the coast salish weaving style of cedar bark. The plan weaves networks of movement and social spaces, creating smaller neighbourhood nodes so people can interconnect. The idea is that the property is “stronger together when it is woven.”

Heather Street Lands, Vancouver

Heather Street Lands. Rendering by MST Development Corporation.

South of Jericho Lands, Heather Street Lands in Vancouver is currently in the re-zoning development phase. The 21-acre mixed-use site, another partnership between MST Development Corporation and the Canada Lands Company, includes rentals, condos and social housing.

As the re-zoning rationale reads, “MST culture and stories are woven throughout the proposed design, and will lie at the heart of the new community.”

At the northern edge, plans call for retail, medical office space and a childcare facility. A First Nations cultural hub faces north to the ocean like the bow of a canoe. “In our cultural customs, when the bow is still facing the ocean, that means it is still ready to go out and paddle.” said Thomas. “It is a symbol that our nation is alive, active, thriving and wanting to prosper.”

Indigenous Hub, Toronto

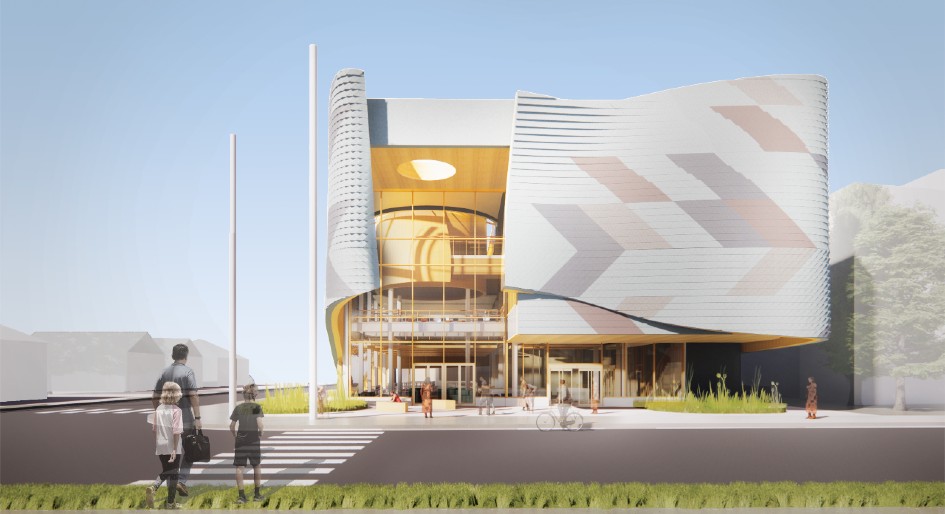

Rendering by BDP Quadrangle.

The official groundbreaking for Ontario’s first mixed-use, purpose-built Indigenous hub took place last summer in the Canary District of Toronto on National Indigenous Peoples Day.

Anishnawbe Health Toronto (AHT), Dream, Dream Impact Trust, Kilmer Group and Tricon Residential are co-developing the site for residential and retail uses,

This will be a new home for AHT and will open as the 45,000-square-foot Anishnawbe Health Toronto Community Health Centre in 2022. The rest of the four-storey hub, including the Miziwe Biik Training, Education and Employment Centre, is slated for 2024 and will be a gathering place for Indigenous people to come together and access vital services like job training, child care and community events.

As design consultant on the entire project Indigenous-owned Two Row Architect developed eight Indigenous design guidelines to articulate Indigenous knowledge, history and values. BDP Quadrangle and Stantec also designed the masterplan.

Woven shawls used in ceremonial dances inspire the perforated metal facade that wraps around the facility, opening to the east to greet the rising sun. Brian Porter said fluid elements of the ground floor “recall pebbles in a stream” to reflect the significance of the Don Valley River nearby.

Much thought went into creating a connection to the ground, a pedestrian experience at the podium and the relationship between the towers and the sky, said Porter. “We appreciate craft; we admire Indigenous constructs like birch bark canoes, baskets, lacrosse sticks and snowshoe. Contemporary buildings should also celebrate craftsmanship.”

Taza Reservoir, Calgary

Taza Water Reservoir at Taza Park Phase 1. Rendering by Zeidler Architecture.

The Taza Water Reservoir will be a gateway feature of Taza Park, which is part of Taza—the largest First Nation development project in North America.

“The reservoir represents the physical return of water from the Glenmore reservoir back to Tsuut’ina land to be redistributed, as well as a symbolic demonstration of Tsuut’ina cultural values and water conservation practices,” says designer Zeidler Architecture.

The pumphouse building aims to be net zero and educate site visitors about water conservation at Taza. Upon completion, it will provide an ongoing and safe supply of drinking water, replace aging infrastructure and facilitate the Tsuut’ina Nation’s current utilities within their infrastructure improvement program.

A partnership between the Tsuut’ina Nation and Canderel, Taza is located near fully-established communities in Calgary. Three distinct villages will rise upon 1,200 acres of land.

Taza Park, to the North, will bring office, tourism and entertainment facilities, residences and a smart farm to the area over the course of its 15-year buildout. On the border of neighbouring Calgary, Taza Crossing will be a central hub that supports entrepreneurial and high-tech industries and businesses, bringing new employment and educational opportunities to Tsuut’ina and the Calgary region.

At Taza Exchange, the Shops at Buffalo Run, with anchor tenant Costco, is scheduled to open in fall 2022. “As we looked at the site, we wanted to make it so we could incorporate culture into the built form,” said Bryce Starlight, vice-president of Taza Development Corp. “We looked for opportunities to incorporate the rolling foothills into the exterior facade, as well as some Indigenous artwork that is appropriate and connected to Tsuut’ina.”

Some of these elements are the buffalo, represented throughout the canopies as a symbol of “stability and taking care of your people. ” The underside of another canopy was revised to reference with a block-gradient aesthetic of a real eagle wing, the eagle being “aspirational and visionary.”