CMHC’s 2024 Rental Market Report, released earlier this year, attracted significant attention by underscoring just how urgently Canada needs more rental housing. Recording the lowest national vacancy rate since the 1980s at 1.5 per cent, the latest data paints a sobering picture of our current housing reality.

“Even in a G7 country that consistently ranks amongst the best in the world, the problem persists,” writes Mathieu Laberge, Senior Vice-President, Housing Economics and Insights for CMHC, in the preface to his recent article, “COVID made housing unaffordability contagious.”

“Even in a G7 country that consistently ranks amongst the best in the world, the problem persists,” writes Mathieu Laberge, Senior Vice-President, Housing Economics and Insights for CMHC, in the preface to his recent article, “COVID made housing unaffordability contagious.”

Here, we share Laberge’s perspective and analysis on Canada’s housing crisis since the pandemic and what he suggests to address the rental housing shortage in the near-term.

Looking back

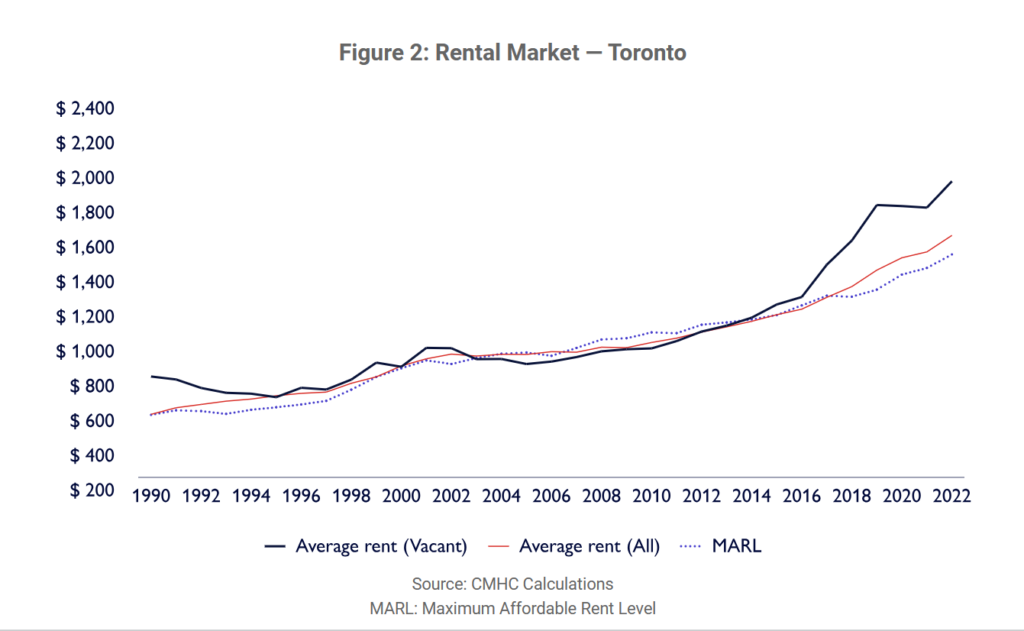

A decade or so ago, households seeking affordable dwellings in central Vancouver or Toronto still had options; they could consider buying a property in a more affordable neighbourhood, or alternatively, they could opt to remain in the rental market for a longer period of time, allowing them to save up for a larger down-payment and thus reducing their future borrowing needs. This led to lower unit turnover in the early 2010s and tighter conditions for those in seek of rental housing.

“We also saw a trickle-down effect for housing as demand spread from central to outer areas of Toronto and Vancouver,” Laberge points out. “This further exacerbated the tight market conditions.”

Then, COVID hit and brought new opportunities. The ensuing lockdowns enabled people to work remotely, which opened avenues for improving their housing situations. Workers were able to move to less-expensive areas, bringing increased demand to housing markets outside of the large urban centres. CMHC’s data shows that affordability started to deteriorate in Montréal, Ottawa-Gatineau, and other smaller urban centres during or just before the pandemic.

As Laberge put it: “Many factors have since contributed to the housing affordability crisis. One could say that COVID helped spread the housing unaffordability contagion across the country.”

Housing unaffordability: an engine for social immobility

While the pandemic sparked increased geographical mobility for many workers, eventually it led to social immobility. According to Laberge, it did this by increasing demand for housing in areas that were not ready for such a large influx of new residents.

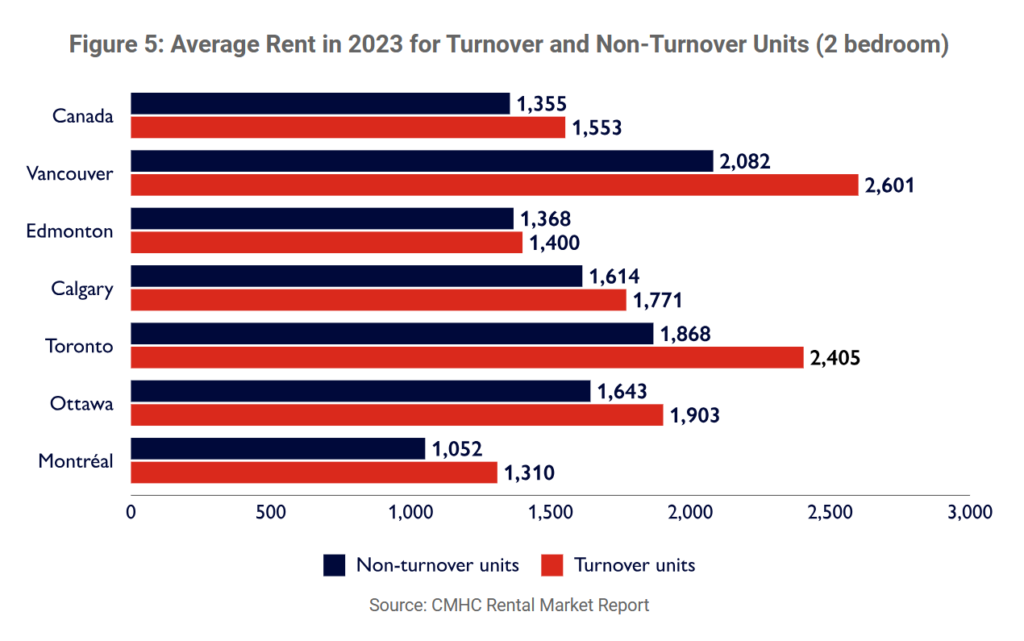

CHMC’s latest report shows that social immobility is taking different forms as a result. While many Canadians are choosing to stay put with their current housing units, as indicated by the lower turnover rates in 2023 (12.5%) compared to 2022 (13.6%), more Canadians are also feeling unable to afford to move to a new home. Whether the decision to remain in place is due to financial stresses or a lack of availability, the trend seems to indicate that renters are increasingly reluctant to move.

shows that social immobility is taking different forms as a result. While many Canadians are choosing to stay put with their current housing units, as indicated by the lower turnover rates in 2023 (12.5%) compared to 2022 (13.6%), more Canadians are also feeling unable to afford to move to a new home. Whether the decision to remain in place is due to financial stresses or a lack of availability, the trend seems to indicate that renters are increasingly reluctant to move.

But there are encouraging signs despite all of this, Laberge argues. For instance, he points out that housing starts in 2021 and 2022 reached historic levels. While starts were down slightly in 2023, they remained well above any average of the past 30 years.

There has also been a structural shift in recent years with apartments growing steadily as a share of total housing starts. Purpose-built rentals, as a proportion of all starts, have dramatically increased from 14 per cent in 2013 to 36 per cent a decade later. Though demand still outpaces supply in the rental market, builders are reacting to tight market conditions and development is on the horizon.

“This is encouraging, but collectively we must acknowledge a key point: new rental housing supply is not necessarily affordable when it is ready for occupancy,” he says. “It may take several years before new supply results in higher affordability. In the short-to-medium term, other options may need to be considered, but they involve rethinking how we envision housing.”

For instance, co-living spaces is one option he feels Canadians of all ages may need to consider. A well-documented phenomenon in cities like New York and London, Laberge argues that sharing an apartment with friends, family, or through organized means could provide an opportunity for better quality housing.

“Converting commercial buildings into residential units often poses technical challenges,” he explains. “The complexity arises primarily from the existing structural elements. For example, because plumbing is integrated into the structure, it becomes difficult to create multiple bathrooms and kitchens on each floor. However, a change in thinking in how some of our housing amenities are used could make conversions more viable.”

When it comes to alternative housing arrangements, Laberge says more research is needed to document how Canadian cities rank compared to their western counterparts and how co-living spaces could help ease housing demand. But, like it or not, he believes compromises in housing needs versus wants may be necessary until supply reaches adequate levels.

“The idea here is not to reduce anyone’s current living standards, but what may come as a sacrifice to some, may very well be a sought-after improvement for others,” he concludes. “The essence of that reflection is to provide new options to Canadian households living through our housing crisis.”