Jobs with high physical demands are understood to result in higher-than-average incidents of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs); however, jobs with high cognitive demand and/or psychological stress have also been linked to increased incidents of MSDs.

It is relatively easy to correlate the implication of high force or repetition to muscular stress; however, studies are now showing that individuals who report feeling high levels of stress are also more likely to report muscular discomfort. Psychological factors such as deadline pressures, lack of control over work, supervision responsibilities and high accountability can impact how the body behaves by increasing applied forces, awkward postures and static loading of muscular tension. To understand how this happens, we need to consider the body’s physical response to stress:

- Increased tension in the muscles: tension in the upper back, neck and shoulders can be found even before manual work activities have started and lead to extended durations of fatigue and discomfort after an employee’s shift ends.

- Less relaxation and recovery: although the physical load on the body may have a specific timeline, cognitive stress doesn’t stop at the end of the workday. After work, muscles remain under stress and are unable to relax, resulting in more hours of tension and decreased blood flow which is a much-needed component to cellular health and healing in the muscles.

- Increased workload perception: those employees feeling mentally overwhelmed often will categorize their jobs as being ‘hard’ and frequently report physical exhaustion at the end of the workday that can lead to higher injury reporting.

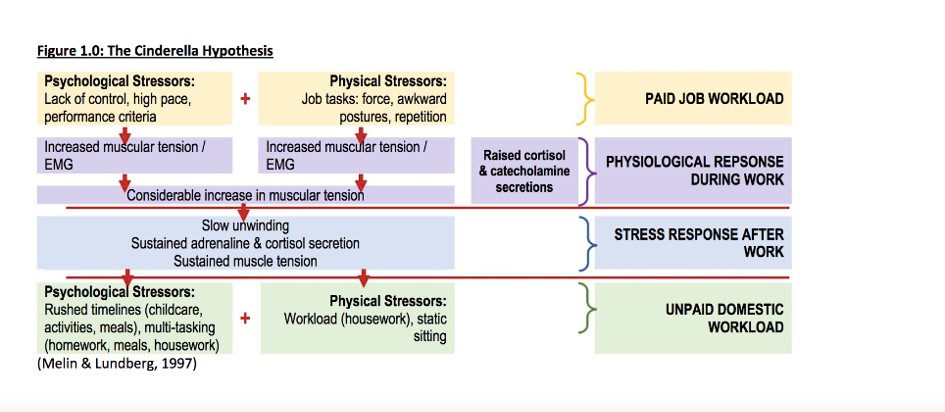

- Increased hormone levels: after the physical aspect of work has ended, the body will still retain high levels of stress regulating hormones such adrenaline, cortisol and catecholamine as shown below in Figure 1.0.

The Cinderella hypothesis demonstrates how all of the above factors when considered together contribute to MSDs, where one factor alone could be overcome; but when stress factors are combined, the effects are cumulative and contribute to stress on the body.

The amount of psychological stress staff underwent over the last 2 years has been significant. Workers have been asked to relocate to their homes, work in small living spaces, give up personal space, blend the lines of work and home, miss out on connections with colleagues and, instead, spouses and children became their co-workers.

That, combined with increased monitoring of productivity and supervision/micromanaging to allow employers to track work progress while balancing concerns of illnesses, disease testing, and potentially poor health, has led to cognitive overload and an increase in psychological stress.

As employers and workplaces pivot once again to return employees to the workplace either full-time or hybrid, they should be evaluating whether they have the infrastructure in place to assist with the psychological effects of the return to the office.

A literary review of 54 longitudinal studies concluded “that psychosocial factors should be considered as independent predictors of onset of MSDs and be relevant to prevention and intervention programmes in occupational safety and health” (Hauke, et.al, 2011). As such, workplaces should be actively working to address the psychological factors for returning to the office to prevent any further increase in MSDs. Some organizations are providing resources to assist with increasing awareness of psychosocial ergonomics and overall psychological well-being:

- Stress Assess App (OHCOW/CCOHS): Asks employees 25 questions pertaining to workload, organizational factors, workplace culture and health & safety.

- Psychological health and safety in the workplace (CSA Z1003-13): Prevention, promotion, and guidance to staged implementation

More and more emphasis is being put on employers to embrace a holistic ergonomic approach, which would include looking to, not only improving the principles of physical ergonomics by reducing physical MSD risk factors, but also tackling the cognitive stressors associated with work. Some excellent starting points would be to:

- Review job descriptions and document the cognitive demands through the completion of Cognitive Demands Assessments (CDAs).

- Provide employee training on ergonomic and mental awareness training.

- Develop an ergonomics and psychological health programs to support employees through both the muscular and cognitive workload.

Through this comprehensive strategy achieving the ergonomic ideals of higher productivity, employee retention and lower MSD injuries may be a reality for employers.

Alexandra Stinson R.Kin., CCPE is a Certified Professional Ergonomist and Co-Owner of PROergonomics. With over 20 years’ experience across North America, she excels in solving diverse ergonomic challenges, lowering injury claims and developing sustainable ergonomics programs, policies and training programs. PROergonomics prides itself on a professional experience that is focused on a proactive, preventative ergonomics model that helps organizations move past a reactive claims-driven approach.