As the original inhabitants of the place that today we call British Columbia (B.C.), First Nations are the holders of thousands of years of traditional knowledge about these lands. Although there is no universally accepted definition of traditional knowledge, the Assembly of First Nations says it is commonly understood as “the collective knowledge of traditions used by Indigenous groups to sustain and adapt themselves to their environment over time.” This knowledge is deeply rooted in First Nations history and culture and is passed down through generations.

Today we often talk about sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” as it has been defined by the United Nationsʼ Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Increasingly, we are discovering the linkages between traditional knowledge and the call for more sustainable practices. Yet, to a large extent, the western world has been slow to incorporate this knowledge into natural management approaches. However, with the growing role of First Nations in the forest sector, the acknowledgement of rights and title, and the leadership of First Nations in land use planning, traditional knowledge is beginning to take its rightful place—assuming a larger role in the environmental conversation among industry, academia, and government.

Matt Wealick is a member of the Ts’elxwéyeqw Tribe near Chilliwack in B.C.’s Fraser Valley. Their territory is over 95,000 hectares and is “rich in Ts’elxwéyeqw cultural history, natural beauty, and resources.” Their mission is “to achieve strength, unity, and success by managing natural and cultural resources for the well-being of our people and our environment.”

Wealick’s family has a long history rooted in the forestlands of B.C. His father worked in forestry, which led him to northern Vancouver Island, where Wealick grew up—deep in the heart of the forest industry. After spending several years on logging crews and as a professional hockey player, he earned his bachelor of science in forestry, and later a master of arts in environment and management. Today he is a Registered Professional Forester.

But his formal training in traditional knowledge began not in university, but in 2002 when he started working with Lennard Joe, general manager of Stuwix Resources, a joint venture owned and operated by eight First Nations in B.C.’s Southern Interior. “It was an eye-opener for me. Up until that time, I hadn’t put a First Nations lens on forest management—it’s not something that we learned in university,” says Wealick. “Through Lennard and community members, I began to learn about the significance of honouring the forests through conducting ceremonies before logging; protecting fish, water, and plants that sustain our people to this day; and the spiritual and cultural values and history of the area.”

In 2004, when the Ts’elxwéyeqw Tribe received its first forest licence, Wealick knew it was time to come home. “Here I was, a professional forester, but I knew I had so much to learn about traditional knowledge and the history of my people,” says Wealick. He spent his first three months on the job going through archives, visiting sacred places, and speaking to community leaders, members, and Elders. “To truly achieve the goals of our people I had to develop a forest stewardship plan that went beyond the regulatory requirements and my university education. I needed to incorporate the Tribe’s values, like water, plants for food and medicine, wildlife, and important spiritual areas—these are things that aren’t legislated but are integral to the survival of our community and all living beings.”

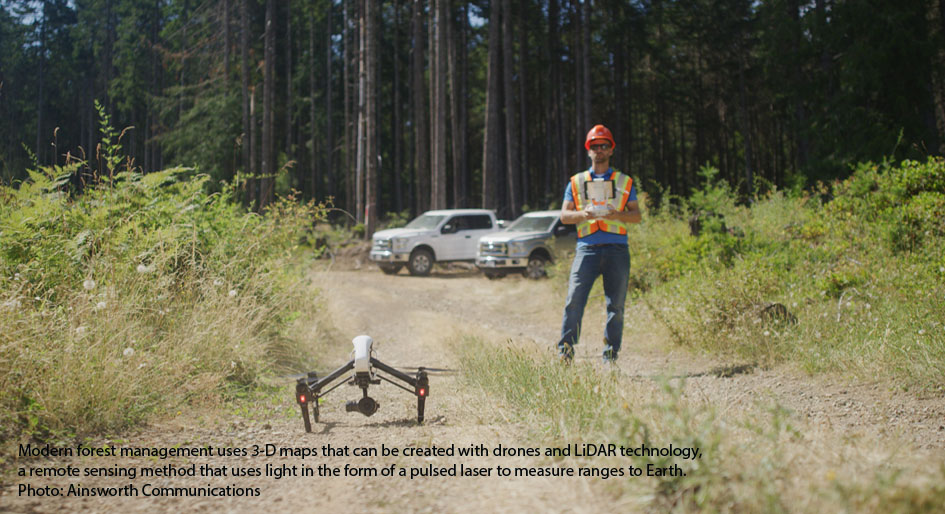

He has since developed a database for many of these values, and is using LiDAR—an aircraft-borne laser scanning tool—to capture much of the forest and plant data which will be modelled into future forest plans and shared with other forest companies operating in the territory.

There are a number of people and organizations who believe, like Wealick, that sharing traditional knowledge with non- Indigenous peoples—who make up 95 percent of B.C.’s population—is integral to sustainability. It’s also something that is on the mind of John Innes, the dean of the Faculty of Forestry at the University of British Columbia.

The university has launched Indigenous forestry initiatives that provide First Nations students with a specialization in community and Aboriginal forestry, but Innes believes more needs to be done to weave traditional knowledge into the forestry curriculum for all students. “When it comes to traditional knowledge, I don’t believe students in North America are getting the knowledge they need,” says Innes. “Our goal is to create a centre of excellence in traditional use and management, with at least half of the instructors being of First Nations descent.”

Forest companies also know that incorporating traditional knowledge is good for the environment, business, and relationships with First Nations. For example, one B.C. company has signed an agreement with the shíshálh Nation that includes a joint decision-making process to ensure that forestry operations uphold shíshálh laws and values. And Canada’s third-party forest certification systems are also embracing the use of and respect for traditional laws—with specific and auditable requirements for forest companies.

Governments are beginning to recognize traditional knowledge in legislation. The Species at Risk Act states that “the traditional knowledge of the aboriginal peoples of Canada should be considered in the assessment of which species may be at risk and in developing and implementing recovery measures.”

Managing our forests and ensuring a healthy planet and communities for generations to come is a goal we all share. Wealick believes it can be achieved by combining thousands of years of traditional knowledge with the professional training of land managers and the latest technology. Both Wealick and Innes agree that twenty years from now, First Nations values and traditional knowledge will be a keystone in natural resource management in B.C. “We have work to do, but we are headed in the right direction,” says Wealick.

Articles like this are featured in a newly released book, Naturally Wood, which showcases B.C.’s sustainable forest management, cutting‐edge wood architecture, design and technologies. The beautifully illustrated, 160-page publication contains more than 65 innovative wood buildings and projects.

Four continuing education units have been developed based on the book. They are recognized by the Architectural Institute of British Columbia and are available at naturallywood.com/naturally-wood-ceus.

Download the Naturally Wood e-book at naturallywood.com/nwbc.